The ‘Old World Order’ is over, but a new one is not inevitable

As Western leaders debate Donald Trump’s demands over Greenland, read Phil Mullan’s speech from last year’s Battle of Ideas festival.

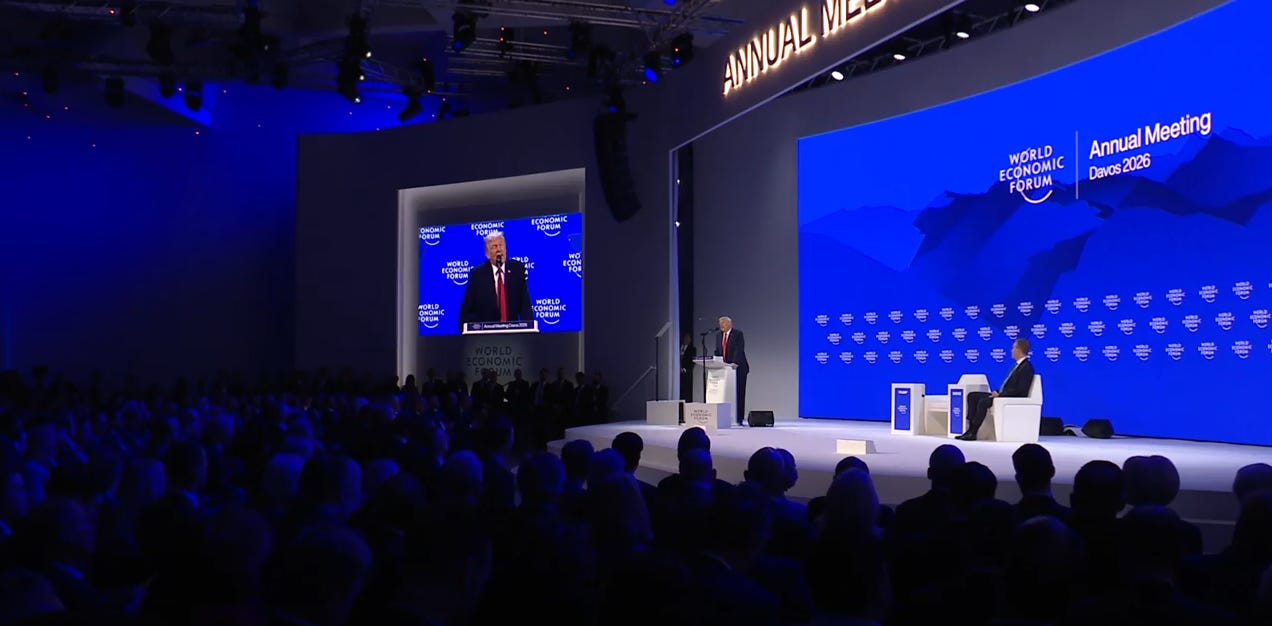

Donald Trump’s demand that America should take over Greenland has caused a furore, with European leaders lining up to restate their support for Denmark’s sovereignty over the island. Things may have dialed down a notch or two in the past 24 hours. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Trump ruled out military action to seize Greenland and suspended his threatened tariffs on Europe. But the fact that Trump has dominated the Davos summit and is so willing to ignore the wishes of supposed allies is the most visible sign that the old ‘rules’ no longer apply.

In his speech in Davos, the Canadian prime minister, Mark Carney, admitted as much. ‘Stop invoking “rules-based international order” as though it still functions as advertised. Call it what it is: a system of intensifying great power rivalry where the most powerful pursue their interests using economic integration as a weapon of coercion.’

But while Trump’s recent actions seem shocking, the decline and fall of the world order has been coming for some time. In a speech at last year’s Battle of Ideas festival, economist Phil Mullan, author of Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents, outlined what has happened and points to a way forward – not to a new, fixed set of international rules but to an environment in which nation states can negotiate their way to an era that emphasises cooperation rather than conflict. As he presciently noted last October, ‘amplifying America’s destabilising influence in the world is its peculiar combination of strength and vulnerability’.

Read the speech below.

There is no doubt that the ‘Old World Order’ is over, but we need to question the other consensus – that we are en route to a ‘New World Order’, to another global arrangement for managing relations between countries, to some revamped rules-based structure, probably with different countries dominating. But this presumption is too restrictive to understand what’s going on now.

The old rules-based order was a specific response to the bloodshed and chaos of the 1930s and 1940s, and it was distinctive also because of the conclusion drawn by the victorious elites of America, Britain and France: that nationhood itself had become a huge problem. With Germany, Italy and Japan in mind, they concluded nations and popular democratic sovereignty could not be trusted; it needed to be constrained by global rules and institutions.

There is nothing destined about that type of top-down international system. Over the past 250 years, such an institutionalised settlement is the anomaly. At best, it only functioned to keep the world reasonably ordered for about 40 of those years, from the late 1940s to the late 1980s. In truth even that stability was mostly due to the Cold War. Heed the truism that ‘history never repeats itself’; there is no necessity for a rule-based scheme to recur.

It is also instructive that the specific phrase ‘New World Order’ was barely uttered outside two specific historical periods. It was first coined by US President Woodrow Wilson at the end of the First World War to frame his proposal for a US-led League of Nations. Yet once the League was set up – famously without America – the ‘New World Order’ idiom fell from use – including during the planning for the post-1945 globalist order. It was as if all the blood, sweat and tears of actually reordering the world was too intense to be encapsulated by those three bland words.

The term only returned to widespread use from the late 1980s, when the post-1945 order started to unravel at the end of the Cold War. We’ve heard it uttered frequently since – by George Bush Senior, by Margaret Thatcher, and by every American president, British prime minister and most other Western leaders.

What these two historical instances suggest is that the phrase ‘New World Order’ has been used mostly when international stability is absent rather than when it actually exists. The ‘new order’ is something desired primarily by the elites of the dominant power or powers as an ideal – and, today, a nostalgic yearning for a top-down organised world that could preserve their privileged positions.

And that’s where we are now. Given the injustices, the illiberalism and the contempt for the demos perpetrated under the umbrella of that expired globalist anti-national order, rather than repeat the mantra new world order, we should instead pursue creating stronger democratic nation-states again. These would enable inter-country relations to be negotiated on a freely decided basis between corresponding sovereign states.

We can help forge this national-democratic objective by addressing the key features of today’s interregnum, while trying to prevent them turning into a barbaric and disastrous conflagration. Here are three aspects of today’s hiatus to be addressed:

First, although domestic politics always interact with foreign affairs, what is new and precarious today is that at home, Western nations are effectively leaderless. This is not just the case in Britain and France; Trump, too, has a national authority problem. A lack of authoritative Western leaders has brought polarisation and conflicts at home, and exacerbated confusions about the national interest. This compounds the danger of arbitrary and unpredictable foreign-policy interventions, likely reinforcing geopolitical fragmentation and international dealignment.

Second, amplifying America’s destabilising influence in the world is its peculiar combination of strength and vulnerability. At least since the 2008 financial crisis, the US has been openly retrenching its world leadership. Although it no longer has the same global authority as earlier, it remains by far the world’s wealthiest country with the biggest military. This makes it a much more influential player compared to the previous interregnum, when Britain was falling from its ‘superpower’ status. But America’s wealth is also fragile because of the country’s vast external indebtedness. This fusion of precarious might creates the tinderbox of America as a muscular and potentially explosive power that is seeking to retain the status-quo with it still predominant.

The third feature is the perilous reluctance of the Western elites to accept the rise of the rest, with the upgrading of many non-Western nations to attain a certain level of power. Again, this is different to the last interregnum, when there were, at most, a dozen significant players around the globe.

Today, economic production is spread across many more mid-sized nations, which means geopolitical influence is also much more widely spread, adding to the complexity of the international configuration. Alongside the rise of China as a superpower, and the economic take-off of India, there are another 20 or so middle powers acting as independent nations – both pursuing their own interests, and also resistant to being told by the West how to act and who to trade with and who not to trade with.

Just these three features, distinctive to our times, imply we are in for an indefinite period of multiple, tangled, fluid coalitions and alignments. To negotiate the complexities of this indefinite era of disorder, and before we can expect to reach any world order again, we need to start by rebuilding strong democratic nation-states.

I think this analysis is too political and too much about the last fifty years. What we are seeing is something much bigger, the rise of China to super power status, the first time this has happened for a non-Western country n the last 300 or so years. The West, without really intending to, gave birth to the Industrial Revolution which required relative freedom to innovate and relative free discussion especially in scientific matters. This would not have been possible had a state authority held absolute power: Italy, the birthplace of the 'new science', became a backwater for two centuries because of the stultifying power of the Roman Catholic Church.

China is a country which has never favoured the individual or economic initiative -- merchants were excluded from power by the literati who staffed the bureaucracy. However, China is overtaking America economically because the new schema of "a capitalist canary inside a Communist cage" as one Chinese thinker put it is singing only too well. This is a very new kind of polity, and is unMarxist in that Marx believed economics always trumps politics. I and many of my contemporaries wouldn't want to live under this new system but the Chinese aren't objecting since it promises to make China dominant world-wide. What's not to like? This is maybe the new schema which will, God forbid, replace democratic capitalism during the next millennium. Trump is a rather desperate and incoherent attempt to turn back the tide and apart from him no one is much bothered, as long as people have their precious smart phones and private cars they'll put up with anything.