The hidden neuroscience of democracy: are we hardwired to reject opposing views?

In a guest post, Barbara Oakley argues that our brains block out uncomfortable ideas that threaten our own view of the world – but that we can learn to be more open, even if we ultimately disagree.

Free speech is a core principle of the Academy of Ideas. In that context, I was delighted to be interviewed for this Coursera online course, Speak Freely, Think Critically. Do check it out.

Whereas at the AoI we view the issue of free speech through the prism of politics, culture, history and philosophy, Barbara Oakley and her team explore free speech, why and how we disagree, through the lens of neuroscience, how our brains work and process ideas. We asked Barbara to explain her thesis, below.

While I’m normally pretty sceptical about using neuroscience to explain social phenomena, I think this is well worth reading and considering – and anything that encourages debate and openness to alternative viewpoints is a very good thing.

Claire

Picture this: you're scrolling through social media when you come across a political opinion that makes your blood boil. Before you finish reading, your brain is already composing a rebuttal. That instant rejection? It's not a character flaw – it's your brain doing exactly what evolution designed it to do. And it's quietly undermining democracy in ways we're only beginning to understand.

In our new Coursera online course, Speak Freely, Think Critically, we take a broad-ranging ‘neuro-historical’ approach to something remarkable: the biggest threat to free speech isn't necessarily authoritarian governments or corporate censorship. It's the fast, automatic circuitry inside your own head.

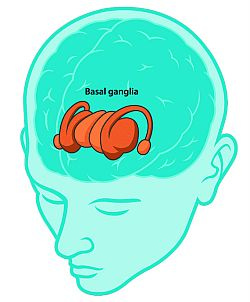

Deep in your brain lies a structure called the basal ganglia – a powerful network that operates outside your conscious awareness. Think of it as a neural gardener. Over time, it learns to nourish familiar, rewarding thoughts even while it lets challenging ideas wither on the vine. Every conversation you’ve had, every headline you’ve scrolled past, trains this gardener in what to encourage and what to ignore

When someone challenges your deeply held beliefs, the basal ganglia doesn’t stop to evaluate. It redirects mental energy away from the discomfort – often before you even know it. What feels like reasoned dismissal can simply be reflexive avoidance. That’s not a bug in your thinking. It’s an ancient survival feature. But in today’s ideas-rich world, it can sabotage civil discourse.

Here’s the paradox: democracy asks us to do something our brains find deeply unnatural. It expects us to consider viewpoints that feel wrong, to engage with people who seem threatening to our worldview and to change our minds when presented with better evidence.

The fourteenth-century scholar Ibn Khaldun understood something of this tension. When he was lowered in a basket from the city walls of Damascus to negotiate with the conqueror Tamerlane, he embodied what democracy demands: the willingness to step outside our fortress and meet the other.

Ibn Khaldun believed strong societies depend on unity. But in this modern era, we also realise that without room for dissent, that unity calcifies. Democracies survive on balance: enough cohesion to hold together, enough openness to keep evolving.

Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), uses the metaphor of ‘rhetorical fortresses’ to describe how we defend our ideas from incoming threats. To understand this concept more deeply, imagine a greenhouse dome over your mental garden. Some panels are clear; others are darkened or sealed shut. It’s not just that threatening ideas don’t get in. It’s that we’re not even aware we’ve blocked them. We might think we're being objective and open-minded even while our brain is systematically filtering out anything that might disturb our existing beliefs.

Social media supercharges this filtering. Algorithms show us what we like, training our inner gardener to reject everything else. When repeated narratives show up across different sources, our brains interpret them as consensus. Researchers call this ‘manufactured consensus’.

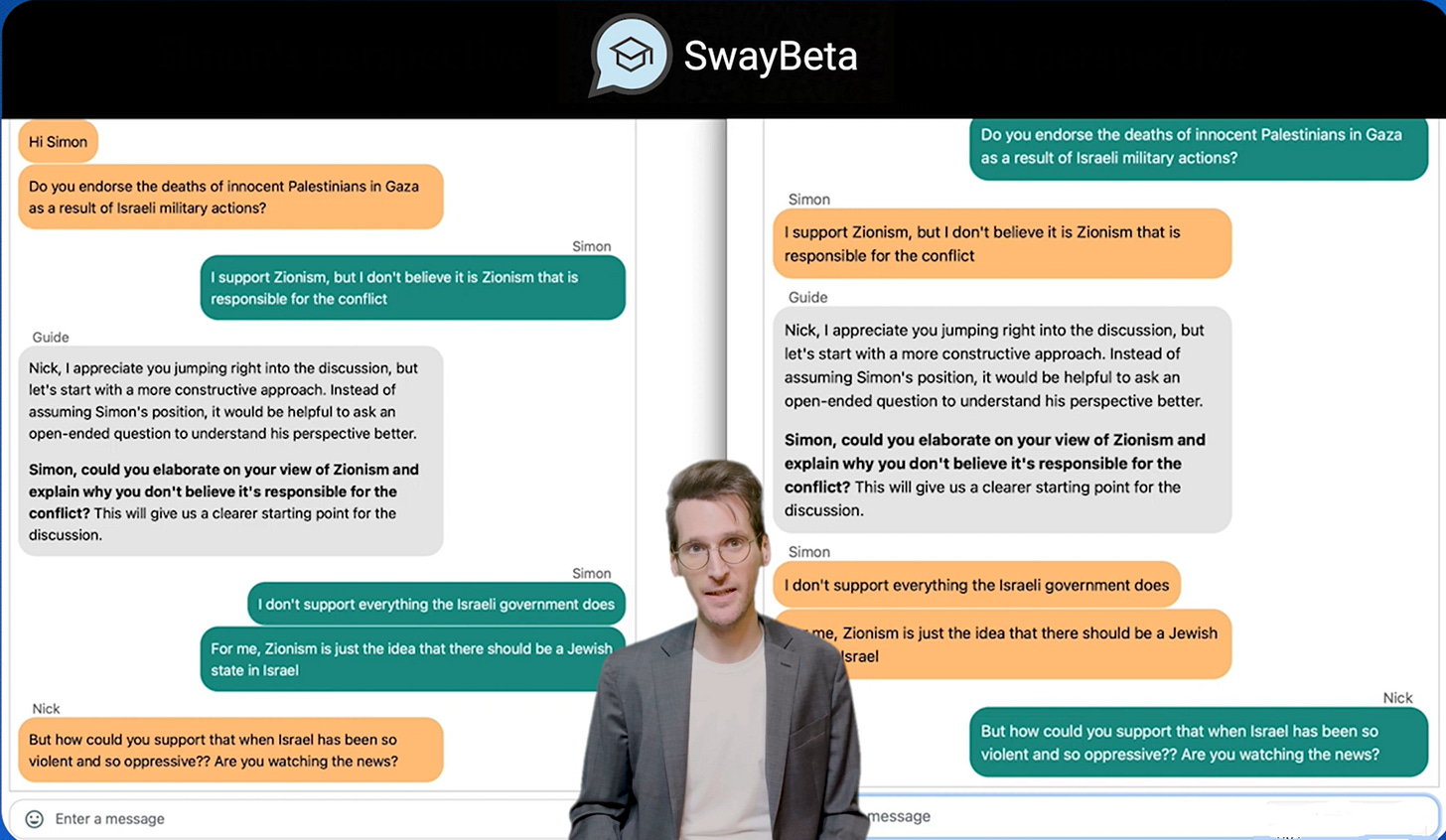

But here’s the hopeful part: we can learn to override our knee-jerk defences and actually hear one another – even when we disagree. To help with this process, our course introduces Sway, an AI-based tool that lets users practise hard conversations. Think of it as a gym for democratic discourse. You’re not trying to win or convert. You’re learning to stay present, to engage, to build what we call ‘intellectual immunity’.

The course also revives something ancient: the art of emotional self-command. George Washington famously battled his own temper, turning to the Stoic philosopher Seneca for guidance. Seneca warned that anger divides, not unites.

Modern neuroscience agrees. When we're flooded with anger or disgust, our rational circuits shut down. But like musicians training their fingers or athletes their reflexes, we can strengthen the circuits of reasoned restraint.

The next time a viewpoint enrages you, don’t rush to respond. Get curious. Ask yourself: how did they come to believe that? Not as a trap, but with genuine interest. Disagreement, when handled well, becomes a civic skill, essential for democracy, not just education.

This matters now more than ever. In a world where AI systems learn from us, our capacity for respectful dissent shapes the future of information itself. If we can't model thoughtful disagreement, how can we expect the machines we build to do any better?

Every time you pause before reacting, every time you ask someone to explain rather than condemn, you’re not just having a better conversation: you’re practising democracy.

Barbara Oakley, PhD, PE is a professor of engineering at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan and Coursera’s inaugural ‘Innovation Instructor’. Her work focuses on the complex relationship between neuroscience and social behaviour. Speak Freely, Think Critically is available now on Coursera here.

Is this in essence the difference between a purely emotional and a purely rational response?

It is often difficult to cut through a debate using emotion with a rational argument?