Are patriotism and the nation state back?

Bruno Waterfield reflects on flags, national pride and George Orwell in this write-up of his contribution to our Battle of Ideas festival discussion.

Whether it’s the seemingly unstoppable rise of national populist parties throughout Europe, or the popular MAGA support for Donald Trump’s pursuit of national interest, it seems that unapologetic nationalism is in the ascendant.

At this year’s Battle of Ideas festival, we asked, at a time when many feel an increasing sense of isolation, of being disconnected from any larger shared project, is a return to national identity an inevitable, even welcome trend? Or does it simply reflect an absence of alternatives, a feeling that ordinary people have little else to hold on to? Does nationalism still retain its worrying, discredited associations with everything from racism to warmongering? Or is nationalism a return to our democratic roots, a force capable of forging national solidarity that can overcome the divisive fragmentation of demographic, cultural, ethnic, identitarian and political changes that have left citizens feeling like strangers in their own land? Can political elites learn to love their country again, and allow national interest to guide policies in the best interest of their nation state?

In this guest Substack, Brussels correspondent for The Times and member of our panel, Bruno Waterfield, shares his opening thoughts and contributions.

For most of us, for most of our lives, patriotism has been more or less innate. We have not needed to really think about it - it is in our bones, our souls. It is the warp and weft of our daily life, especially the golden threads of how we make sense of the world and the lived traditions, cultures, geography, feelings, sensibility and essence of how we live our lives with others.

Probably the best exploration of British or English patriotism is George Orwell’s The Lion and the Unicorn - written in 1940 and published in early 1941, as Britain faced a war for national survival. Orwell made the point that, while not as exotic as Spain, Englishness or Britishness was as individual and distinct:

‘It is somehow bound up with solid breakfasts and gloomy Sundays, smoky towns and winding roads. It has a flavour of its own. Moreover it is continuous, it stretches into the future and the past, there is something in it that persists, as in a living creature. And above all, it is your civilisation, it is you. However much you hate it or laugh at it, you will never be happy away from it for any length of time. The suet puddings and the red pillar boxes have entered into your soul. Good or evil, it is yours, you belong to it and this side of the grave you will never get away from the marks that it has given you.’

Eighty-five years later, we know what Orwell means - and while some of the examples or flavours might have changed, many have not. We get it. This is a truth.

What we also understand is that something has really changed beyond the inexorable ‘progress’ that most of us are rightly sceptical of. When Orwell wrote that the threat to how we live was external, he was referring to Germany and the threat of invasion by a totalitarian military power. Today, the threat is internal, from the intelligentsia and a middle-class clerisy - especially in London, where they run the commanding heights of the bureaucratic apparatus, including the police, that seek to run our lives.

This internal threat is hostile to the key tenets, principles and foundations that sustain us as well as our communities - havens in a heartless world - our families, our freedom. The stakes are high.

So, to flags. If you look back at photographs of ‘Last Night of the Proms’ from 10 years ago or more, the Royal Albert Hall is a sea of waving Union Jacks and Flags of St George. Here are the British great and good - as I’m sure they would be the first to agree they are - waving the flags of the established order to the tunes of Victorian imperial Britain.

Then look at photographs taken this year or in recent years; the venue still hangs up some Union Jacks, but the audience is a sea of blue flags circled with gold stars. Today’s ‘Last Night’ audience are still great and good, but now they have a new flag - the European flag.

This is the flag against the people, who had the gall, the uppityness and lack of deference to vote for Brexit - the greatest popular challenge to the established order since universal suffrage.

The meaning is not in a mere flag, but in who waves it and why they do so. This is seen explicitly in recent ‘raise the flag’ furore, as Union Jacks and flags of St George went up on lampposts across the country. The outrage this caused was telling. If the hoi polloi, the plebs and the nation wave the flag that is most likely regarded as racist litter or graffiti, it will be seen as an unpleasant and vulgar intrusion on our green and pleasant land that must be tidied up as quickly as possible.

If the same symbols are flown at the Cenotaph or above a royal palace, they are still officially establishment - even if the ‘Last Night’ brigade have ditched it and our right-on clerisy is uneasy. If unofficial and popular, the Union Jack or cross of St George fluttering from lampposts in Kent, Essex, the Midlands, Lancashire or wherever, are at best rubbish and - at worst - the march of racist thugs.

If there is an acceptable Union Jack par excellence it is that on Sir Keir Starmer’s ‘Brit Card’ as an official emblem of the state. That is the official place for it. It belongs to them, not us.

It is ok to be ‘patriotic’ in an official, state-licensed sense for a bodged ID card plan. It is still there at the establishment pomp of national rituals, such as Remembrance Day or Trooping of the Colour, which are still popular too - although much less fashionable among the middle classes. But when the flags appear autonomously, without official permission, it is to be feared and stopped.

It is not the national flags that are the problem, it is us, the nation. The establishment has not dispensed with national flags but cannot bear for the common people to take them as their own.

This is a problem because true British patriotism, in terms of our lived democratic, civic and free traditions - which go back centuries, constituting the nation - is unofficial. Patriotism is inseparable from the life of the British peoples. It is popular, not state-licensed or official.

A bit more Orwell:

‘All the culture that is most truly native centres round things which even when they are communal are not official – the pub, the football match, the back garden, the fireside and the “nice cup of tea”… It is the liberty to have a home of your own, to do what you like in your spare time, to choose your own amusements instead of having them chosen for you from above. The most hateful of all names in an English ear is nosey Parker.’

Again some of the outward forms have changed - firesides are long gone in net-zero land and pubs are under siege - but the essence, the sense of truth, is still palpable.

That last point about the nosey Parker is important. In the 21st century we have new communal forms, as the chats at the school gate become a WhatsApp group set up by parents, or the Facebook site for the street, village or town.

Think of the cases, which come thick and fast, of squads of police officers arresting a parent for criticising a schoolteacher on a school chat group, or the arrest of a comedian by armed police for airing his opinions. You can see what we are up against. We are in the sights of the senior police officers, much of the public sector, employers, magistrates, universities, schools and a whole army of people trolling, scouring through social media to uncover wrongdoing. We are battling a wannabe tyranny of ‘nosey Parkers’.

This way of dealing with debate in our communal life is still, thankfully, alien to the vast majority of us. One of the abiding patriotic values we have is fairness, which is a set of ethics or traditions attached to freedom and tolerance. It has distant roots in Christianity, the sectarianism of the reformation, the English Civil War and the battles for free speech and universal suffrage of past two centuries.

It is almost unconscious, but you can chart back much of our ethical framework, which is communal and still strong, to Hobbes and Locke, to King Charles I, the roundheads, Levellers and Cromwell, to Burke versus Paine, the Chartists and the spawning of our radical or conservative political traditions. Perhaps the strongest of our tenets or traditions is the idea and practice of freedom of thought (religion), with emphasis on keeping force out of politics or communal, moral, and private life.

With centuries of an identifiably British ethical tradition, there has never been popular support for the use of force or violence to settle communal questions. Fascism or other totalitarian political ideologies such as Stalinism have never had proposers outside small circles of the intelligentsia or tiny groupuscules of football hooligans looking for a bigger purpose in their lives.

To rewrite British history as a litany of violence, slavery and oppression is to erase the historical reality of the emergence of popular traditions based on and forged through the struggle to preserve and conserve communal living free of force and officialdom. Echoing the sensibility evoked so lyrically by Orwell, Trevor Phillips wrote a piece in the Times about the ‘Unite the Kingdom’ march last month: ‘These are the people you meet in a country pub with their dogs, or in a queue for drinks at half-time. They conjured the spirit of the cheerful British amateur, draped in a variety of flags - the cross of St George, the saltire, the Welsh dragon and, of course, the Union Jack’, he wrote. ‘If LS Lowry were to paint the scene on Saturday, his canvas would be called something like “Middle Britain on a day out in London”’.

This brings me to the question of whether the ‘nation state’ is back? It is not.

The ‘Brit Card’ state is alive and well, with squads of police knocking at a door over a social media post. This is against the nation.

The answer or remedy lies in our civic, ethical traditions and, especially, our votes. Here can be the source of a renaissance in our nation - based on patriotism - and campaigns to reconstitute institutions in our image, not theirs, to reintroduce accountability.

Voting, and the struggle for universal suffrage in Britain, has historically been about conserving, defending and protecting our way of life. It is defined as we want to live it rather than moulded in the image of the social engineer enthroned in the commanding heights of authority, from the Malthusians of 200 years ago to the ‘woke’ progressives of today.

For the Chartists, who are so tangled in roots and traditions, a major struggle was to preserve the family, which was broken up when men, women and children were put in different workhouses by the ruling guardians and magistrates. Marriages were smashed, ‘whom God hath joined together let no man part asunder’ no longer applied. The Chartists and radicals wanted the vote, universal suffrage, free speech and rights of association, to reverse the Malthusian Poor Laws that were disrupting and destroying the basis of their lives.

Our history on this island was always about principles of political equality and democracy against a minority, defined by their outlook of moral superiority to the mass of the nation or peoples. It was a struggle against the rule of oligarchies, the magistracy and officialdom, in the form of instructors or guardians.

This is not about trying to revive an identity with the British state - or its traditional ceremonial pomp - but a project of making institutions of authority accountable to us, making them public, national and representative of us and our communities. The nation state needs to be rebuilt.

Bruno Waterfield is one of the longest serving newspaper correspondents in Brussels for The Times. He has been reporting and commenting on European affairs for over 25 years, first from Westminster and then from the capital of the EU. He reported for the Daily Telegraph from Brussels from 2006 to 2015. He also writes on European affairs in his Substack.

This essay is based on a speech and contributions in the discussion ‘Are patriotism and the nation state back?’ at the 2025 Battle of Ideas festival.

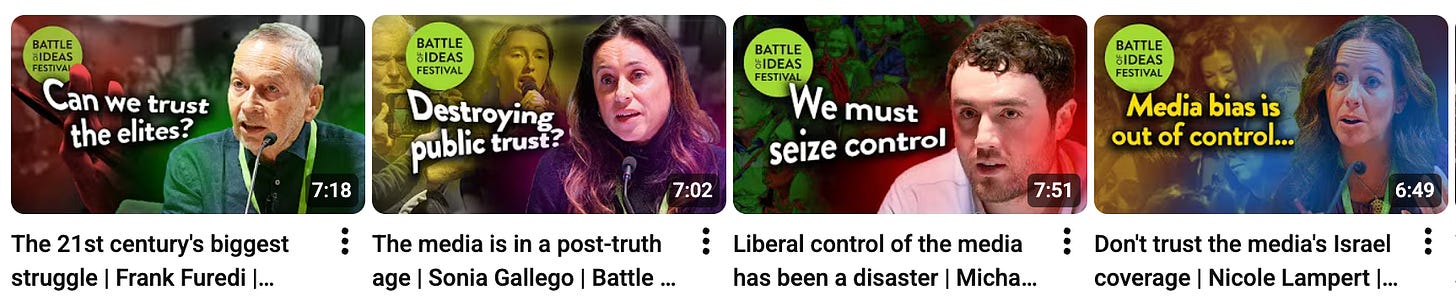

Watch all introductory speeches from this keynote discussion filmed by Worldwrite:

You can watch debates and discussions from all our festivals by subscribing to our YouTube channel here, or listening to our podcasts on our audio archive here.

I love Ms Fox. She is a bastion of common sense and free speech and is a national treasure for the UK.

The theory which technocrats seem to proffer is that we are in a transitional period during which the rules of accountability and the democratic responsibility of the governors to the governed must be suspended. Because of mass migration, globalized business, foreign students, etc. the native culture no longer has right to assert itself. The enlightened technocrats are farsighted and wise and they will beat the distinctiveness out of "the English," in your case, while excusing the culture of the migrants and creating generic, bland public spaces and institutions. In this way they justify everything from diversity mandates to high inheritance taxes, etc.

Your understanding of democracy is much more just, I think. But every time I talk to a supporter of the EU or mass migration, they identify totally different problems from the ones I see. They want a kind of Year Zero wipe of the distinctiveness of a country if it offends newcomers or if it leads to attachments (old boys club). They are so wrong, but they believe so earnestly in this ambitious project, it is strange to argue with them.