A tribute to Nicolas Kinloch

Nicolas was an inspirational history teacher with a passion for knowledge and debate - the Academy of Ideas will miss him.

We were very sorry to hear of the passing of our good friend, Nicolas Kinloch. Nicolas was a history teacher in Cambridge, much loved by his students and colleagues. To us at the Academy of Ideas, he was a great thinker and defender of his subject - he spoke at our Battle of Ideas festival, wrote a Letter on Liberty for us in defence of teaching history and lectured at The Academy on the Civil Rights movement. His passion for history was evident, and he saw the task of passing on his knowledge and expertise to the younger generation as a great privilege, as well as a responsibility. Nicolas was inspirational to those who met him, and we are very sad to lose him. All of us at the Academy of Ideas send our thoughts and best wishes to his family and friends.

In honour of Nicolas, we wanted to dedicate this Substack to his work at the Academy of Ideas and the charity Ideas Matter. Read and listen to his contributions to debates about racism and free speech, history and the difference between teaching and activism.

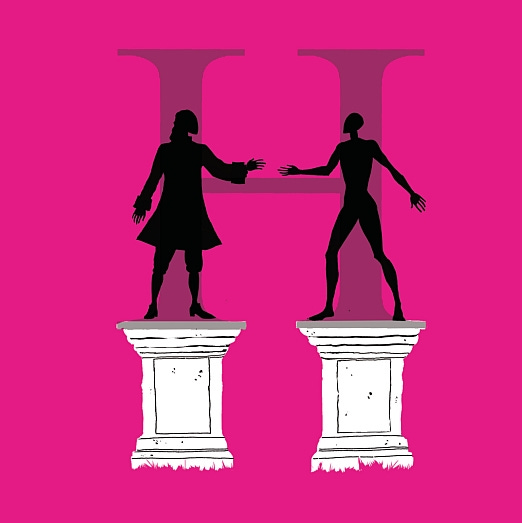

History Wars - Battle of Ideas festival 2021

How should we decide what works of literature, art and history form the ‘canon’ in our curricula, and which historical figures should we choose to adorn our establishment buildings? Are today’s students really too sensitive to live and learn alongside Britain’s past, to appreciate that today’s moral standards are different to those of our ancestors? And how big is the issue of calls for decolonisation? Is the idea that the school or university curriculum should rely on codified knowledge of the past simply a desire to maintain the status quo?

Speakers: Nicolas Kinloch, Dr Sean Lang, Dr Alka Sehgal Cuthbert, Sean Walsh and Chair: Kevin Rooney.

The Academy Online II: race and racism

This is a lecture by Nicolas Kinloch on ‘The use and abuse of the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement’, given at The Academy Online, Saturday 28 November 2020.

The emergence of Black Lives Matter has been accompanied by renewed interest in the American civil rights movement that made such an impact in the 1960s. But what are the key attributes of that movement, and how should we assess today’s interpretation of its history and legacy?

In Defence of Teaching History - a Letter on Liberty

History has long been the most controversial of all subjects on the school curriculum. No one seems to worry very much about what children are taught in geography, drama or even science (although this may be changing). History has always been different.

What children should learn about the past, and how they should learn it, has invariably been the subject of considerable disagreement. In the 1970s, advocates of the so-called ‘New History’ demanded that the analysis of source-material replace the ‘rote-learning’ of the past. The widespread triumph of this approach helped ensure that, for a generation of pupils and teachers, the acquisition of historical knowledge was deemed relatively unimportant. In a startlingly short space of time, all this has changed. Knowledge - and a heavily racialised version of it, at that - is again at the forefront of the historical curriculum.

The culture wars have arrived in schools. It was to be expected: schools have long been at the heart of a progressive consensus. There has always been an element of school leadership which asks itself whether it should be ‘doing something’. This was evident long before last year, and the re-emergence of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Nor is it surprising that a growing number of schools in Britain - among the most self-consciously progressive institutions in the country - have adopted, largely uncritically, the tenets of Critical Race Theory. Unsurprisingly, this has not saved them from being denounced as hotbeds of institutional racism.[i] One inevitable consequence of this shift in thinking within schools has been the demand for changes to the curriculum - particularly in history. That demand might previously have been focused on diversifying the curriculum, but no longer. Today, the call is to decolonise it.

Dead, white men

‘Decolonising the curriculum’ sounds like a laudable activity. After all, virtually everyone agrees that empires and colonialism are bad (although for true progressives there are some exceptions to this rule - indigenous empires, and even China, are usually

given something of a free pass.) According to one claim: ‘Decolonisation is crucial because, unlike diversification, it specifically acknowledges the inherent power relations in the production and dissemination of knowledge, and seeks to destabilise these, allowing new forms of knowledge which represent marginalised groups - women, working classes, ethnic minorities, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender to propagate.’[ii] A little later, the authors express it more simply: the purpose of decolonisation is to remove the influence of dead, white men.

This conviction often accompanies several others. If you believe that the Enlightenment was a racist undertaking, designed to provide a justification for slavery and empire, it follows that its principles are inherently flawed. Historical research, and history-teaching, should be activist enterprises, with the clear purpose of dismantling hegemonic power structures. Not all history teachers believe all these things. But some do, and, as self-proclaimed activists, they tend to have a disproportionate impact on developments within education.

The need to see victims everywhere requires a very particular view of the past, and an understanding of human beings and their societies as essentially static.

Even until fairly recently, historians and history teachers were mostly agreed that true objectivity, while perhaps impossible to achieve, remained a desirable ideal. This is not the view of modern social-justice activists or their adherents. The difficulty of achieving objectivity is seen as a reason to dispense with it altogether. And since all agree that there can be no such thing as an apolitical curriculum, many are comfortable replacing what they see as a hidden bias with an overt one. Some go further still: that the very notion of objectivity is a construct of white supremacism. To attempt impartiality is to operate from a position of privilege. Instead, history, like other subjects, should now open itself to other, less privileged ‘ways of knowing’. It must free itself from the ‘tyranny of the written word’.

Paradoxically, the relentless focus on race, slavery and empire can appear to confirm the idea that it is what Europeans and other white people do that really matters.

You might think that this would be a difficult undertaking in a subject which relies so much on documentary evidence. You might even imagine that the existence of the written word, far from being tyrannical, is the very reverse, and is an essential resource to help free us from the more burdensome impositions of legend, speculation and received wisdom. You would be mistaken. A demand for written evidence is increasingly viewed as itself clear proof of reliance on a tool of white supremacy.

Calls for the abandonment of ‘privileged ways of knowing’ are part of the ever-growing primacy of ‘lived experience’. The term ‘lived experience’ is exclusively applied to the experience of oppressed or marginalised groups or individuals. It is not generally open to any questioning at all, let alone serious challenge. Attempts to do so are perceived as further efforts to silence such groups or individuals, and often establish the questioner as a would-be oppressor. Whatever the intention, the result is to diminish history as a genuinely critical enquiry.

Under the principles of decolonisation, the main quality needed by the new subjects of the curriculum is a claim to victimhood. To be a victim is one of the central requirements of identity politics - this is not difficult, since many more people can claim this status than might be expected. The need to see victims everywhere requires a very particular view of the past, and an understanding of human beings and their societies as essentially static.

Although all people of colour count as victims, they are often of interest only insofar as they remain so. The overall result is that they tend to be denied much independent agency, seeming only ever to respond to what white people do. Paradoxically, the relentless focus on race, slavery and empire can appear to confirm the idea that it is what Europeans and other white people do that really matters. It can become quite difficult to examine any non-European society in its own right, since doing so would let slip another opportunity to explore and denounce an example of racism.

When is an empire not an empire?

A good example of the tendency to see indigenous societies as essentially unchanging is demonstrated by the various studies of Native American peoples undertaken by many schools in England. Few people would deny that, in general, Native Americans suffered atrociously at the hands both of white settlers and the US government. Their status as victims, past and present, appears undeniable. This is not enough, however, for some teachers who hold a romanticised view of indigenous peoples as somehow possessed of innate moral superiority. This view is often couched in the language of environmentalism.

For many, Native Americans represent a sort of ecological ideal - they are seen as people who tread lightly on the land, leaving, as the saying has it, only footprints. One popular school exercise consists of getting pupils to appreciate how many uses Native Americans had for a bison carcass. The message is quite clear: indigenous people may (regrettably) have been carnivores, but at least they used every bit of the tiny number of animals they consumed. White Americans, by contrast, drove the bison to extinction, just because they could. In reality, Native Americans who were given the opportunity also killed large numbers of bison. There is, indeed, some evidence to suggest that the bison population was in decline well before the industrialised slaughter of the late-nineteenth century.[iii]

Progressive lore generally holds that only white people are capable of oppressing anyone.

In general, indigenous reality was often rather different to the ideal promoted in schools. Although some Native American groups may have been content to exist in a kind of primeval, unchanging Eden, many were not. A number even embarked on an imperialism of their own. To take just one example, the Lakota, or Sioux, were relatively insignificant until, taking advantage of modern technology represented by the horse, they moved onto the Great Plains. But they did not move into an unpeopled wilderness, as some textbooks imagine. Like the white settlers who would replace them, they attacked and attempted to expel those who were already there.

One author of a recent book even went as far as to suggest the establishment of a Lakota empire in the early decades of the nineteenth century.[iv] Few modern progressives ask why other groups, such as the Pawnee and Crow, chose to quickly ally themselves with the forces of the US - to defend themselves against their Lakota oppressors. To the Pawnee, the Lakota were known simply as the ‘throat-cutters’. It would be hard to discover this in a modern textbook, since progressive lore generally holds that only white people are capable of oppressing anyone.

From MLK to BLM

It used to be unusual to study any aspect of the history of the US. In English schools, there were courses entitled ‘modern world history’, but these might more accurately have been called: ‘selected areas of central and Eastern Europe 1914-45.’ Few students looked at much American history, and fewer still looked at the whole history of that country.

In recent years this has changed, though the broad outline is still uncommon. Most students who do study America look at the civil-rights era, and there are excellent reasons for doing so. The civil-rights struggle of the 1950s and 1960s is an inspiring story, with largely clear-cut heroes and villains. It seems to confirm Martin Luther King’s claim - it was not original - that the arc of history bends towards justice. Progress is hard to deny: from segregation and persecution, to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the emergence of African Americans into every area of American life. No wonder, then, that many teachers have adopted it as a course of study.

The very idea that African Americans have made any kind of progress has now become unacceptable, at least to those grounded in Critical Race Theory.

No wonder, too, that many people whose knowledge of race relations (whether in the US or Britain) is largely limited to America in the 1960s, see in the BLM movement the lineal descendants of the civil-rights movement. But however understandable their desire not to find themselves ‘on the wrong side of history’, they are mistaken. Black Lives Matter - the organisation, rather than the slogan - has little, if anything, in common with the civil-rights movement. There are a number of reasons for this confusion.

Many teachers, nowadays, tend to view the past in largely secular terms. It was why the re-emergence of radical religion in the twenty-first century was met in schools, for the most part, with simple incomprehension. Few had anything to say. The study of the civil-rights movement is another example of this. Teachers and their students generally underestimate the role of churches, which played a crucial role in the lives of African Americans. The movement is interpreted as the struggle of activists who were motivated by the same things that pre-occupy people today. This inability to accept that people in the past may have been different underlies much of today’s activism. There is a tendency to assume that the mental world of the past can, and indeed should, be judged by one criterion. Did it correspond, in every way, with the preoccupations and assumptions of twenty-first century liberal progressivism? If not, it is to be ignored. If that proves impossible, it is likely to be condemned.

It is not just the religious dimension of the civil-rights movement that renders it increasingly ‘problematic’, to use a favourite activist word. The very idea that African Americans have made any kind of progress has now become unacceptable, at least to those grounded in Critical Race Theory. The non-violence espoused by the movement is seen as an irrelevance. Even in schools, the same amount of time and attention is paid to groups such as the Nation of Islam and the Black Panther Party (which were never part of the civil-rights movement) as to King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. Calls by BLM activists in Britain for a black militia suggest that it is the Panthers, rather than the civil-rights movement, which have captured the imagination of young people.

The civil-rights movement proceeded in the hope that, at some future point, race and skin colour would not matter. Today’s activists believe precisely the opposite.

The American founders of BLM describe themselves as ‘trained Marxists’. Marxism was quite alien to the civil-rights movement, which was militantly hostile to communism. The reason was not difficult to find - most African Americans of the period were patriotic. Many, like the assassinated Mississippi leader Medgar Evers, had served during the Second World War. What they wanted was for America to live up to its ideals. They would probably have been surprised to be told that the US was in fact a racist project from its beginning, as some argue today.[v] They certainly had little use for Marxism, and where Marxists infiltrated the movement, they were expelled from it upon discovery.

Above all, the civil-rights movement, founded on the principle of redemptive love, sought reconciliation and integration. None of this is palatable to today’s activists. The civil-rights movement welcomed the participation of white people, some of whom lost their lives in the struggle. BLM generally regards white people as racist, whether they know it or not. In 1963, Martin Luther King dreamed that the sons of former slaves would sit down with the sons of former slave-owners at the table of brotherhood. BLM dreams that the great-grandsons of former slave-owners be identified, publicly shamed, and compelled to pay reparations. The civil-rights movement proceeded in the hope that, at some future point, race and skin colour would not matter. Today’s activists believe precisely the opposite. Race, skin colour and identity are all-important, and people - especially white people - who do not think so, and who claim to be colour-blind, are perhaps the most dangerous racists of all.

Reclaiming the classroom

Where next for history in schools? This is not easy to anticipate, but some developments seem likely to continue, and indeed to accelerate. Trends in fiction may point the way. It is increasingly accepted by the social-justice movement that people ‘stay in their lane’. By this they mean that it is unacceptable for writers to adopt even a fictional identity that they do not share. It is quite conceivable that history-teaching will come to be viewed in the same way. In a society increasingly obsessed with issues of identity and race, there is much truth in Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s observation that, ‘some [people] are viewed as part of oppressive groups, some as part of oppressed groups. A person’s individual actions can generally do little to change the immutable characteristics of the tribe to which they belong’.[vi] It is easy to see what might be on its way: demands that only black people teach black history; that only women, or those identifying as such, should teach women’s history, and that only Muslims can teach the history of Islam. It would be ironic if a form of segregation were to be introduced into societies which had never experienced it. But it is not at all unlikely.

What, as Lenin famously asked, is to be done? Governments might ban the teaching of Critical Race Theory, as they have in several American states. But it would be very easy for teachers to continue to teach it if they so wished. Any who were stopped would probably be considered martyrs in the cause of educational freedom. And while it is possible that a significant number of teachers might rebel against an ideology that tells pupils that they are born to be either oppressors or victims on account of their skin colour, there can be serious consequences for dissenting from any orthodoxy - especially from one that deploys the vocabulary of progressivism. Few history teachers, I suspect, will find it easy to declare themselves opposed to theories which claim to oppose racism, empower the marginalised and challenge the privileged. Nor is the power of fashion to be underestimated. For all their claimed espousal of critical thinking, teachers are as likely as anyone else to succumb to the lure of the popular, especially if they can feel virtuous for doing so.

But history is not just about race and victimhood; nor is it a mere collection of simple moral tales. Indeed, its importance lies precisely in that it has so many different, and sometimes conflicting, stories to tell. Some of these will speak directly to students’ own experiences. Others will lead them into strange and different worlds, where people thought and acted very differently. In these worlds they will need guides who have made at least some effort to learn the local language and customs. History teachers, indeed, rather than activists.

References:

[i] Schulz, Freia ‘British schools are institutionally racist. That must change fast’, Guardian, 24 March 2021

[ii] Begum, Neema and Saimi, Rima, ‘Decolonising the Curtriculum’, Political Studies Review, 17 February 2018

[iii] Isenberg, Andrew C, The Destruction of the Bison: an environmental history, 1750-1920, Cambridge University Press, 2000

[iv] Hämäläinen, Pekka, Lakota America: a new history of indigenous power, Yale University Press, 2019

[v] The 1619 Project, New York Times, 14 August 2019

[vi] Hirsi Ali, Ayaan, ‘Tribalism has come to the West’, UnHerd, 10 May 2021

Nicolas Kinloch was educated at Reigate Grammar School, and read modern history at the University of Liverpool. He was head of history and professional tutor at the Netherhall School and Sixth Form College, Cambridge, where he also taught Russian. He was a teacher fellow at the School of Oriental and African Studies, teaching in Sweden, Estonia, Japan and Kazakhstan. He was formerly a deputy president of the Historical Association, of which he is an honorary fellow. Nicolas was also a regular contributor for many years to BBC History Magazine and is the author of several books.